Commonplace Books

AC recently had a book giveaway and I am the lucky recipient of an advanced reading copy of Michael Dirda's Book by Book. It's a lovely size for the bike bag and has turned out to be the perfect lunchtime reading. I haven't gotten far into it as I suffered a bout of reader interruptus, but what I have read thus far I have enjoyed. The book appears to be made up of little essays, thought fragments, observations, and favorite quotes. Actually there are quite a lot of quotes. Dirda mentions in the introduction that he keeps a commonplace book. Which got me thinking. I keep a commonplace book too. Since I started blogging though I have not been very good at using it and quotes I don't put into blog posts sort of slip by. It also doesn't help that I thought I'd get fancy and start keeping my quotes on my computer instead of wire-ringed notebooks. Now I've got quotes in two places and I haven't quite figured out a satisfactory organizational method for my online quotes. But that's only part of it. I realized that once I put a quote in my notebook, I rarely go back and read it. Once in awhile I flip through, stopping at places that catch my eye. I do this maybe once or twice a year. And I am always surprised and delighted by what I find. If such browsing gives me pleasure, I am puzzled as to why I don't do it more often. I'll leave figuring that out for another day. I thought I might do some flipping and share some quotes.

- A reader reading makes the book, brings it into meaning, by translating arbitrary symbols, printed letter into an inward, private reality. Reading is an act, a creative one. Viewing is relatively passive. A viewer watching a film does not make the film. To watch a film is to be taken into it--to participate in it--be made part of it. Absorbed by it. Readers eat books. Film eats viewers. Ursula LeGuin, The Wave in the Mind

- Time comes into it./ Say it. Say it// The universe is made of stories,/ not of atoms. Muriel Rukeyser, "The Speed of Darkness"

- Take care you don't know anything in this world too quickly or easily. Everything/ is also a mystery, and has its own secret aura in the moonlight, it's own private song. Mary Oliver, "Moonlight"

- "Making money isn't hard in itself," he complained. "What's hard is to earn it doing something worth devoting one's life to." Carlos Ruiz Zafon, The Shadow of the Wind

- An adventure is only an inconvenience rightly considered. An inconvenience is only an adventure wrongly considered. G.K. Chesterton, "On Running After One's Hat"

- To live content with small means, to seek elegance rather than luxury, and refinement rather than fashion, to be worthy, not repectable, and wealthy, not rich, to study hard, think quietly, talk gently, act frankly, to listen to stars and birds, babes and sages, with open heart, to bear all cheerfully, do all bravely, await occasions, hurry never--in a word, to let the spiritual, unbidden and unconscious, grow through the common. This is to be my symphony. William Henry Channing

Art has not yet come to maturity unless it is practical, moral, and connected with the conscience. It should "make the poor and uncultivated feel that it addresses them with a voice of lofty cheer."

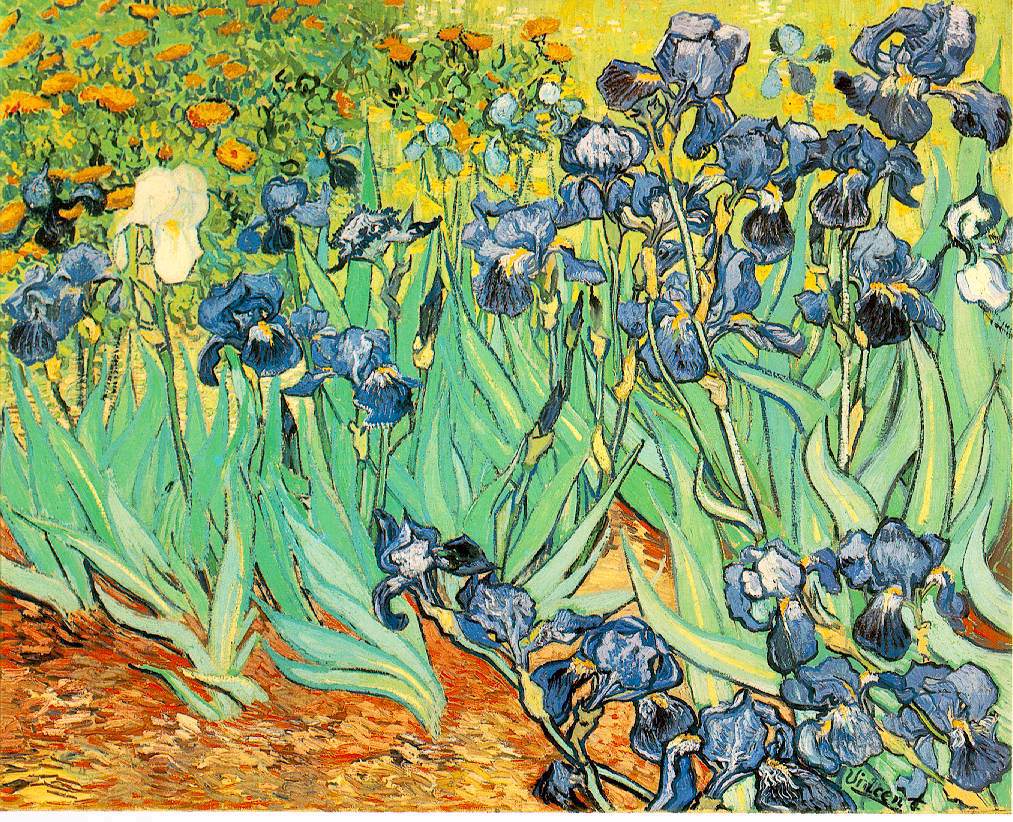

Art has not yet come to maturity unless it is practical, moral, and connected with the conscience. It should "make the poor and uncultivated feel that it addresses them with a voice of lofty cheer." once at the Getty museum in California. The painting made me weep. Much of Van Gogh's work makes me cry. I don't know much about Van Gogh and I am not sure that if I did it would make a difference. All I know is that his art stirs me up. Maybe it is the beauty that does it and I'm going to have to get my hands on Elaine Scarry's book On Beauty and Being Just that

once at the Getty museum in California. The painting made me weep. Much of Van Gogh's work makes me cry. I don't know much about Van Gogh and I am not sure that if I did it would make a difference. All I know is that his art stirs me up. Maybe it is the beauty that does it and I'm going to have to get my hands on Elaine Scarry's book On Beauty and Being Just that